I remember when I was a little girl I took a motorhome trip with my father. One night I insisted I sleep by myself in a tent outside. I wanted to feel alone in the wilderness.

“You’re not going to like it,” he said, exasperated. But, as always, he let me learn my lessons on my own. it sticks with you better that way.

That night was the coldest of my life. I woke up with ice for bones. My joints ached to bend and I longed to return to the motorhome. I broke myself free form the tent after much deliberation only to find the door to the motorhome locked. He must have locked it without thinking. I banged and banged on that door to no avail until I eventually slinked back to my lowly tent to await the morning. Since then, camping for me has always been associated with the bitter cold.

A little (much) later, in college, a few friends invited me on a camping trip to the Blue Ridge Mountains in Georgia. I asked if it would be cold and they assured me I wouldn’t.

“Bring a light jacket at most,” they said.

To their surprise, not mine, it rained and then snowed that spring break in the mountains. Almost immediately upon our arrival. Despite my asthma, I built our fire int he rain and then snow as they held a tarp over the pit and my sopping hair as if it were a veil.

Never once have I found camping miserable, only darkly humorous. I’ve found living difficult moments like this is something learned. Over small things, I am a complete nut. I can worry about anything that shouldn’t be worried about. But when it comes to hypothermia, count me in for the “experience” of it all.

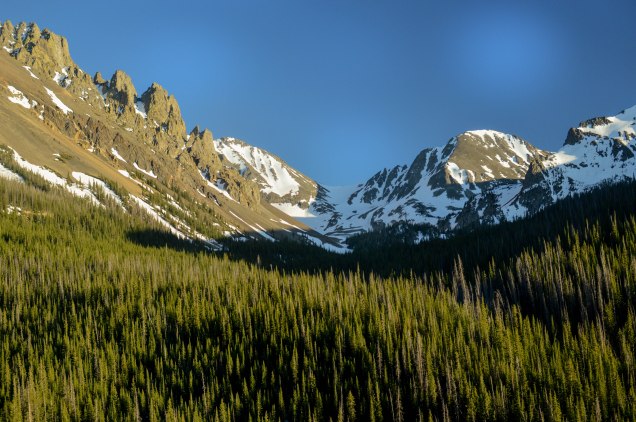

This morning I awake in the rockies on the side of a small cliff, ten crusted with ice. I put my pants on in my sleeping bag, make a small fire by my tent, and squat over it for a while to warm my backside. It’s the calmest I’ve felt in weeks.

Camping alone is a certain type of boring. For most of it, I forget consciousness and I meet my needs. There’s collecting firewood, making a shelter, eating. None of this requires much thought. I spend a lot of time sitting and staring like, I imagine, other animals do. Without service, without people or music or anything that could interfere with my just-being save a book, I’m in a rare state of complete non-performativity. I am so largely defined by how I want to be perceived that the impact of this state on my actions and thoughts are insidiously omnipresent. I strain to be who I want to be instead of who I am. Camping alone, I forget to be me.

Steinbeck, in his travelogue Travels with Charley: In Search for America, also noticed this shift in self-perspective when he was alone. He called it a reversion to the pleasure-pain basis. “The delicate shades of feeling, of reaction, are the result of communication, and without such communication they tend to disappear.” Steinbeck is wary about isolation, concerned only with how it “diminishes the subtlety of feeling” that comes with social performance.

Right there: social performance. That’s the difference between Steinbeck and I. What he calls subtlety of feeling I call performance. One insists on the sincerity and selfhood of this state and the other insists it is a mere performance of an identity. As someone who has been to more new schools than grades, I’ve always known how to adapt my identity. I did this to the point where I didn’t know what my identity was other than a fluid that moved from social circle to social circle, molding to their shape.

But it’s not only this experience that has shaped me in this way. Social media has also done this to all of us: all of our interfaces implore the performance of self in a multiplicity, as if bundled together they are the verb-form of a fractal mirror. Analysis turned inward is a constant for those of us who use regularly tune in to social media. The irony is, this analysis is often directed to the inwardness we are trying to project, and not our inwardness at all.

And so I go camping. I: not-bored, not on display. Completely myself. It’s wonderful.